Venetian Glass

Broken but Beautiful

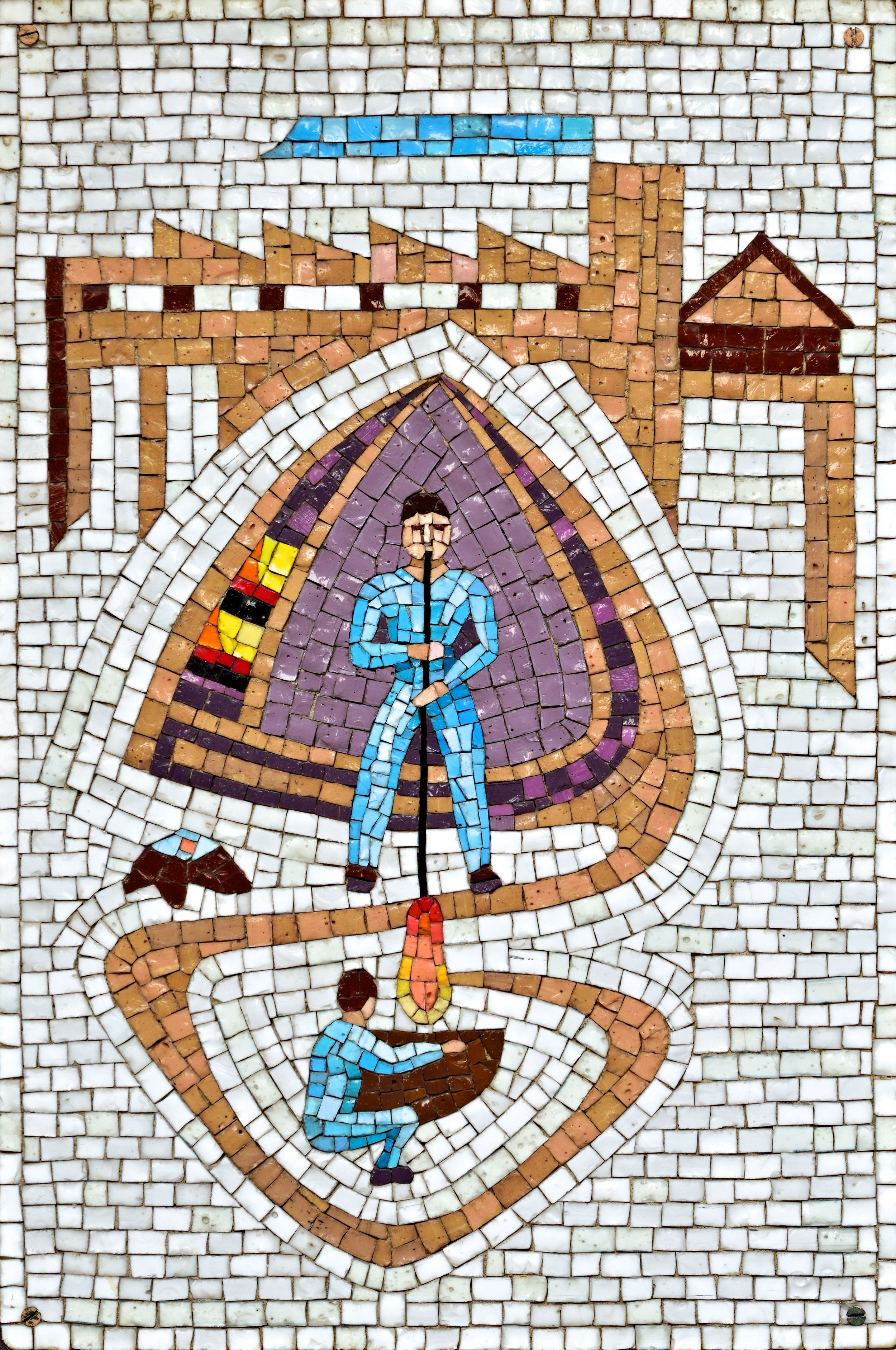

Figure 1. Venetian mosaic mural in Murano showing glass making.

The history of Venetian glass is a fascinating tale of wealth, poverty, and renewal. Since the Middle Ages, it has been world famous and was a primary export for the Venetian Republic (697–1797). Purity of ingredients created glass that was crystal clear while proprietary recipes created striking colors. When combined with glassblowing techniques that had been handed down for generations, Venetian glass was superior to all other glass. Everyone wanted it – and everyone wanted to know how it was made (Figure 1). The Venetians held a monopoly on high-quality glassmaking for centuries, developing or refining many technologies including optically clear glass (cristallo), enameled glass (smalto), glass with threads of gold (aventuien), multicolored glass (millefiori), milk glass (lattimo), and imitation gemstones.

Today the Venetian Glass industry is centered on Murano, a collection of islands just outside of Venice. Of the approximately 30 glass factories which remain on the island, two, Mosaico Dona’ Murano and Orsoni, continue to create smalti for use in art or architectural mosaics.

There are two types of smalti. The first is colored smalti, made from a potassium-lead or sodium-based glass with metallic oxides, which produce a vast range of colors, and an opacifier, usually tin oxide or a mixture of feldspar and fluorspar. The later mixture produces a dense and durable hard glass with a deep brilliant color, perfectly suited for mosaics. These ingredients are melted together in the furnace and either poured into a puddle of molten glass (also known as a “patty” or “pizza”) or pressed into slabs from an eighth to a quarter of an inch thick (Figure 2). After slowly cooling, the slabs are cut into small bits (tesserae) with the aid of a small hammer or a guillotine-like machine (Figure 3). The second type is metallic smalti, which is basically two layers of glass with gold or silver leaf sandwiched in between. The metallic tesserae are then cut with a glass-cutters wheel.

Figure 2. Venetian glass "pizzas" prior to being cut into smaller tesserae.

Figure 3. Venetian glass tesserae.

The cut edge of the glass is typically used as the surface of a mosaic. In the Byzantine tradition, however, it is the sharp broken edge of the tesserae that forms the surface of the finished mosaic. This produces the luminosity typical of Byzantine work. In some 20th century work, the full glass patty is used, broken into random shapes, or set into the bedding mortar and broken in place. Use of the top or bottom surface of these larger pieces of glass creates a bold, colorful statement.

Regardless of type or method, Venetian glass is, and remains, integral to the history of the mosaic art form.