Briklath

Was it all it’s cracked up to be?

When working on the restoration design for a 1918 mansion in Westchester County, NY, probes in exterior stuccoed elements and interior plastered walls and ceilings exposed an unusual type of wire-and-brick lath, which warranted further investigation and research. The lath consisted of metal wires embedded in fired clay at the crossing points.

Figure 1. Lath and stucco discovered during probes.

Figure 2. Illustration of Stauss & Ruff “wire brick”, from “Ruckblick auf die deutsche Bauausstellung in Dresden,” Schweizerische Bauzeitung vol. 37, no. 3, (January 19, 1901): 28.

The development of wire-and-brick lath began around 1880 when P. Stauss and H. Ruff of Cottbus, Germany, who initially produced a lath consisting of reeds tied together with wire, experimented with thin wire mesh embedded in fired clay. They eventually received a patent for their product in 1889. They called it “drahtziegel” or “wire brick” and marketed it as a fireproof material (Figure 2).

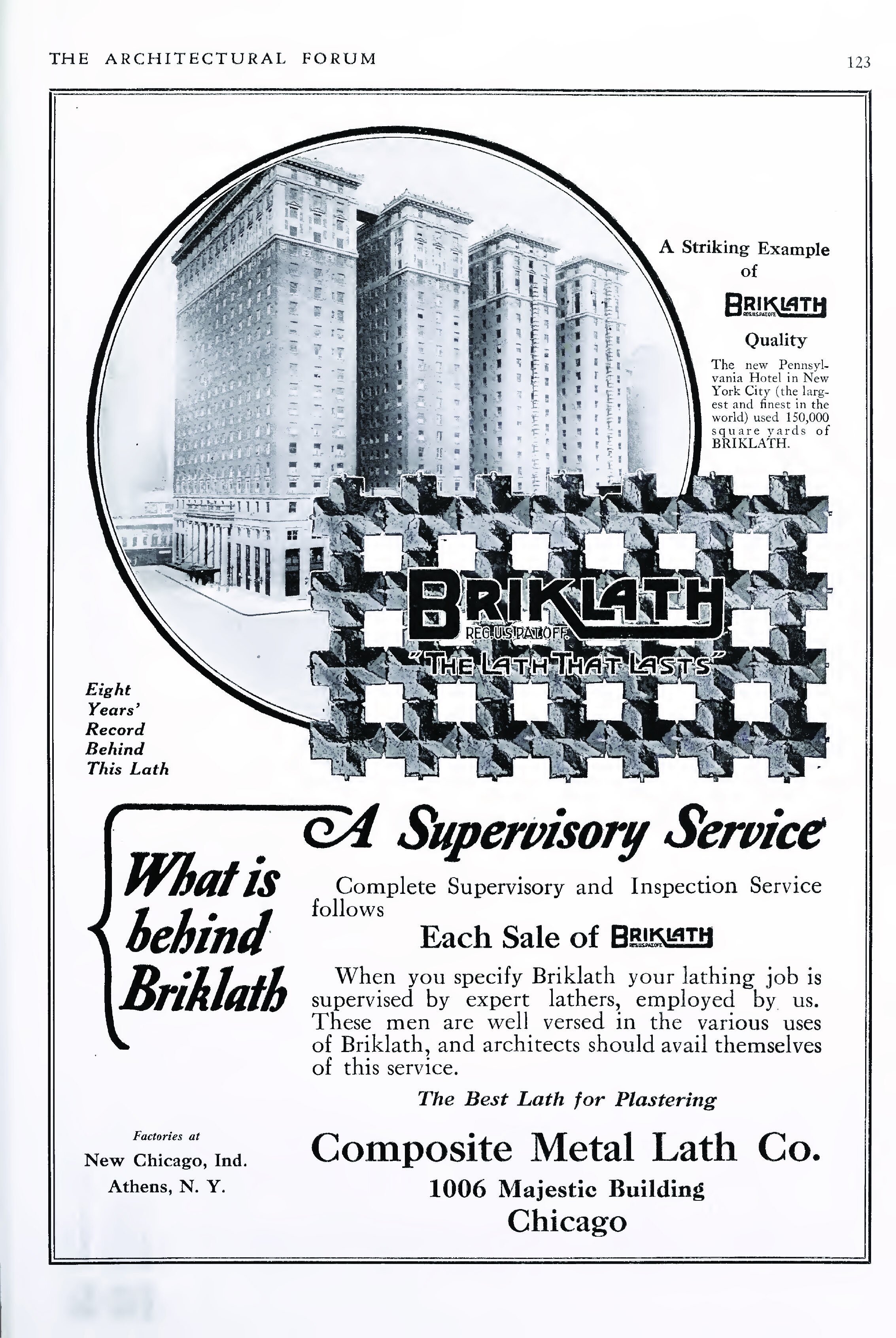

The Composite Metal Lath Company (CML), incorporated in 1912 in New York City, bought the Stauss & Ruff Patent. They described their product as “a square woven mesh of No. 19-gage steel wires upon which brick clay in the form of small crosses or bricklets is moulded.” The advertisements for CML's Brick Lath heralded the material as being strong, capable of forming a tight bond with the plaster due to the brick pieces, resistant to rusting, and fireproof, which was a major concern in the United States at the time. They also claimed that the use of brick lath saved on the amount of plaster, as significantly less material was required to create a proper plaster key than with traditional wire lath. Much more marketing pushing the advantages of this new material continued through the 1910s and, in 1920, the tradename “Briklath” was introduced. Despite all the marketing, the company soon filed for bankruptcy and was dissolved.

Figure 3. Detail of back side of lath showing stucco keys, corroding wire, and spalled bricklets.

The samples of stucco and Briklath removed from the mansion probes verified that, where the few keys remained intact, very little material squeezed through the openings to create keys. However, contrary to the product claims, corrosion of the wire mesh was widespread. Very few complete bricklets remain (Figure 3). Analysis showed that the brick crosses were fired at a low temperature which resulted in an absorbent material. Water infiltrating behind the walls was absorbed by the bricklets, which caused the wire to corrode and in turn spall the bricklets and plaster keys.

Though a relatively short-lived product in the United States, Briklath may be found in buildings and structures from the late 1910s especially in the Northeast and Midwest where the Composite Metal Lath Company operated its plants. 1916 advertisements claimed that the lath was being used on the construction of the of the New York City subway tunnels. In 1917, CML’s brick lath was used to help insulate and protect cables in manholes in New York City. In 1920, The Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City (currently being demolished) was advertised as being the largest use of Briklath in the world (Figure 4).

We hope this small introduction to Briklath gives you some insight the next time you run into it on one of your projects.

Figure 4. Briklath ad from The Architectural Forum (September, 1920): 123.